Conduct Negotiations With The Harvard Concept

Finally gain the upper hand in negotiations.

Everyone has done it before. With friends, acquaintances, strangers, even with your own parents. You may have already recognized it: we are talking about negotiation.

In this article, we want to use an example to look at a successful negotiation and apply the concept of the Harvard method.

Why Negotiate?

It doesn't matter whether we're children negotiating about bedtime, driver license holders about the price of our first car, or senior buyers negotiating the ongoing terms of our suppliers. We always have the goal in mind: to get the best conditions for us. Why should we settle for less than we can get?

A Mind Game

Let's take the latter case as an example. We are part of the purchasing department of a company and are supposed to negotiate the conditions for a partner contract with a new parts supplier. We want to buy as many goods as possible for the lowest possible price in order to be able to produce cheaply and thus increase the profit margin. It is acutely an order for the pilot series of 500 units and possible future contracts for new products. The new supplier currently only knows about the 500 units.

Unfortunately, our parts supplier has a very similar goal. He would like to achieve the best conditions for himself and set the highest possible price, since he will then achieve high sales volume and, as a result, a lot of profit.

This creates a conflict of interest and both parties try to find a solution to the problem. Let us now pursue two of the many possible possible solutions.

Version 1

Everyone sees only their own problem in the conflict of interest. The supplier does not want to fall below the limit of €50/unit and remains on his price position.

Our purchasing team, on the other hand, has set a limit of €20/unit, which must be defended.

There is haggling, threats and maybe even insults. Nevertheless, both contracting parties cannot reach an agreement because they are only sticking to their set goals, price expectations and desired balance sheets.

Dejected, our department is looking for a more "understanding" partner...

The Core Concept Of The Harvard Method

Roger Fisher and William Ury were professors at Harvard Law School and co-founders of the Harvard Negotiation Project. They developed the Harvard concept and published the associated book "Getting to YES" in 1981, which has long been considered the standard work for negotiation methods in German-speaking countries as "The Harvard Method".

Before attempting to solve our problem using the Harvard method, let's take a look at the book's gist.

1. Separation Of The Relationship Level From The Factual Level

What is meant is the awareness that in a negotiation you are not only negotiating about one thing, but are also working on the relationship with the negotiating partner. In order not to jeopardize an ongoing profitable partnership, the result of the negotiations should be viewed as a joint solution to a joint problem and not the contractual partner should be targeted as a problem.

They should try to understand the reasons why their partner takes their point of view and still be very clear about their point of view. Functionality and objectivity are required here. By treating each other in a friendly and respectful manner, alternative solutions can be found together under these circumstances. "Be hard on the matter and gentle on people," says the two professors' book.

2. You Represent Your Interest, Not Your Position

In order not to be severely restricted in the solution approaches, you should not negotiate your position, but your interests. The position is, for example, a price or a number of goods, i.e. the "what" around which the negotiation revolves. Interest, on the other hand, reveals the reason for your actions, i.e. the "why" of your actions.

Be open about their interests and ask about the interests of your partners. This creates empathy and in the same breath much less potential for conflict.

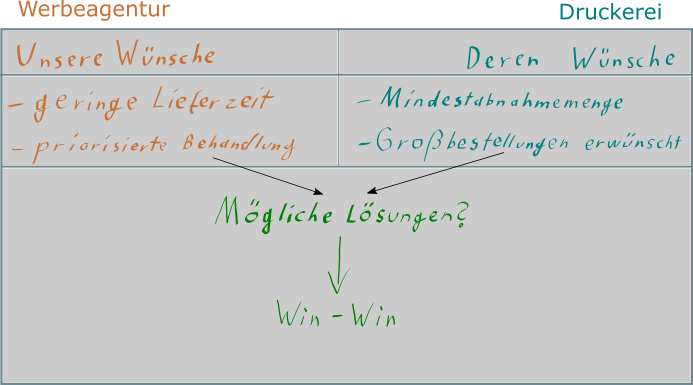

3. Design solution options for both parties

You don't have to agree on a solution right away. Discuss several possible solutions together. Brainstorming to collect all the wishes can help them with this. Then think about how to combine the collected wishes of both parties in different variants.

That way, you have a good chance of finding an agreement that not only both sides agree with, but also that both parties emerge victorious. The Harvard method wants to bring about this win-win situation in negotiations.

4. Objective Criteria Lead To Agreement

In order to avoid haggling over cents and pennies that would damage your relationship, it is advantageous if you do not rely on personal sensitivity when weighing arguments or the value of individual wishes, but on generally recognized objective standards. This means, among other things:

- Market comparisons

- Reports prepared by an independent body

- Norms

- State legal regulations

- An impartial mediator

The objectivity of these standards increases acceptance and the sense of fairness of a possible solution.

If None Of That Helps

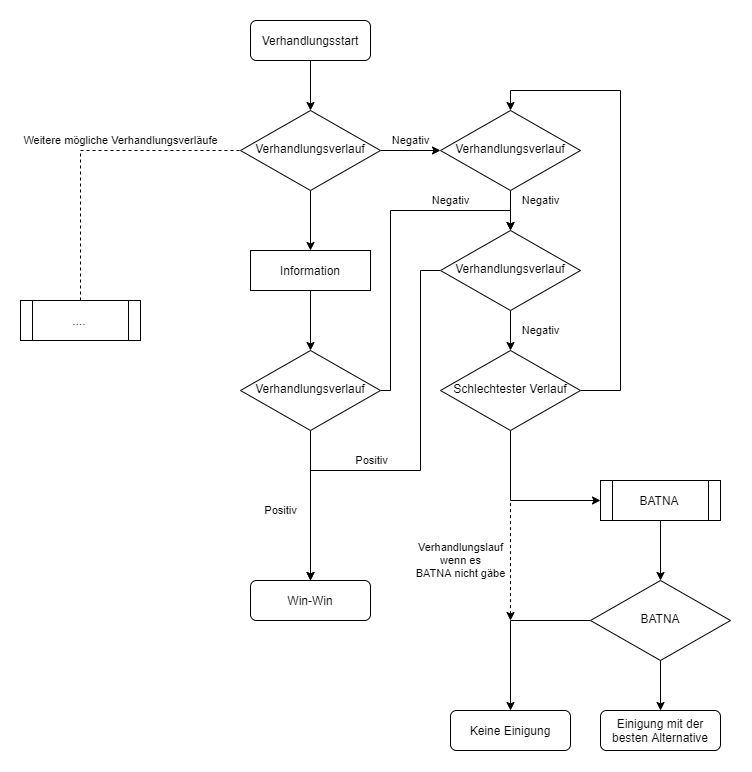

What if the negotiating partner doesn't play along? There are ice-cold business people who don't leave an inch of ground or stubborn heads everywhere. If you really don't see a way to come to a good agreement, you need to know your limitations. The Harvard method provides for one last big joker, the BATNA.

BATNA stands for "Best Alternative To Negotiated Agreement" and means translated: "Best alternative instead of a negotiated agreement".

You should consider one or more alternatives before the negotiations if you cannot reach an agreement with your negotiating partner. This ensures more self-confidence in the negotiation and - should it come to the point that you have to use your BATNA - professionalism.

Use your BATNA if you feel like you might come out of the negotiation with worse results than your BATNA. Please note, however, that your opponent may have also prepared a BATNA.

Example - Variant 2

Now let's rewind our example using the Harvard method.

Variant 1 was about the position of the price of €20/unit. Our interest, on the other hand, is actually to find a very reliable delivery partner who will also prioritize any short-term orders.

Before the negotiation day, our department agrees on a BATNA: If the supplier is absolutely not interested in a longer cooperation or seems unable to deliver reliably, we will offer him 32€/unit for this order, as well as a second order for another project with greater margin for the supplier.

The negotiation begins. The seller of the supplier is warmly greeted by three of our employees with a cup of coffee or tea and asked about his arrival. We inform the seller of our interest in finding him a partner for our new product line. We assure you that we are unfortunately somewhat budget-bound in this project, but this is not the norm in our company. Since we are about to start production, we ask if the delivery of the 500 units would be possible in just 3 weeks if we get together.

The seller replies that this would mean an enormous organizational effort and that he would have to charge a surcharge for the short time window. He estimates €50/unit.

We are amazed at his statement, since we checked the market price for our components in advance, but we don't want to get involved in haggling over the price. We ask why he sets the price so high and whether the surcharge is absolutely necessary.

As an answer we learn that the production management of the delivery company is busy planning a new production line, as a new hall is being built. Therefore, the production management is only available to a limited extent.

Since this sounds like an increase in production capacity, we ask whether the capacity of the new line is already planned and find out again that this is only 40% full.

We then disclose the information that we are planning further product series whose components we could obtain from him and promise him further contracts if he agrees with us in the current project with price and delivery time. In order to be able to produce for the time being, 200 units would be enough for two weeks. Only then are the last 300 required.

Unfortunately, this statement is not enough for the seller, as he needs something more concrete. We then offer him not only to place this order with him, but also to conclude a cooperation agreement, which means a long-term partnership and long-term profit for both companies. The seller pricks up his ears because he has been instructed to find more customers for the new production capacities.

For us, the contract would give us a prioritization of order processing, even for short-term prototype orders, and would secure long-term profits and work for the supplier. The condition is the successful completion of the currently required order of 200 parts in 3 weeks and the remaining 300 parts within the next 2 weeks.

We agree on €28/unit and make an appointment to discuss a cooperation agreement.

Conclusion

We have now seen from this fictitious negotiation that it can make sense to question the reasons and interests of the negotiating partner. We treated the seller kindly and dealt with his problem. We avoided direct position negotiations by questioning interests and were able to find a solution for both sides. We used the cooperation agreement, a well-known instrument, to reach an objectively fair agreement.

However, we are fortunate that the seller was so accommodating that we didn't have to use our BATNA. Fortunately, this was also a relatively easy negotiation. don't you think so?